From rising temperatures and sea levels, to desertification and extreme weather events, climate change presents a global crisis that requires global collective action. The science is clear: without concrete and decisive climate action, we stand to lose a lot. This crisis not only puts natural sites around the world in danger, but also our abundance of shared cultural history and heritage. To save our World Heritage, we need to mitigate climate change.

“Change minds, not the climate”

Mitigating anthropogenic climate change, including more frequent and intense weather events, requires large-scale transformative change and serious climate action from all sectors of society. The most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability” (Pörtner et alii 2022), highlights the explicit interdependence and intersections between the Earth’s climate and natural systems and human societies.

UNESCO has released a wide body of literature encouraging the world to mobilise together to mitigate the worst of climate change, stating in its 2019 publication “Changing minds, not the climate!” (UNESCO 2019,b), that the climate crisis is the “challenge of the century” and that we are in a “race against time.”

The climate crisis has the potential to radically alter all aspects of life as we currently know it. A crisis of this scale requires all sectors of society, not only those directly related to climate research or policymaking, to work together to mitigate the greatest effects of climate change. UNESCO explicitly highlights and encourages this shared responsibility to action, stating:

“The climate crisis is not only threatening our ecosystems, it is also undermining fundamental rights, widening inequalities and creating new injustices. That is why ethical imperative must guide our action. Beyond the political and legal agreements essential to preparing for the future, change involves a shift in mindset, a different way of considering the place of humans in nature. This challenge mobilises all resources, including education, research and creativity. It is an ethical and humanistic commitment. This is UNESCO’s mandate, and it is a matter of urgency” (UNESCO 2019,b).

A wide array of threats, including terrorism, armed conflict, and climate change, risk compromising the continued preservation or, in some cases, the existence, of World Heritage properties around the world. As expressed explicitly in the UNESCO Climate Policy Document, “Updating of the Policy Document on climate action for World Heritage”,(UNESCO 2021,e), climate change has become one of the most significant threats to both natural and cultural World Heritage Properties, with the potential to impact their Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), including their Authenticity and Integrity, as well as their capacity for local economic and social development. According to UNESCO:

“Outstanding Universal Value means cultural and/or natural significance which is so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and to be of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity. As such, the permanent protection of this heritage is of the highest importance to the international community as a whole” (World Heritage Policy Compendium. See also UNESCO 2021,a).

Nevertheless, the topic of climate change as a legitimate and large-scale threat has only recently been a consideration of UNESCO and other international bodies.

A major goal of the UNESCO World Heritage List is the continued commitment of States Parties to conserve cultural and natural heritage around the world, so as to preserve and share these cultural legacies with future generations. The 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage stipulates that the “…deterioration or disappearance of any item of the cultural or natural heritage constitutes a harmful impoverishment of the heritage of all the nations of the world…” If sites are not adequately prepared, or serious climate action fails to be implemented at the local, national, and international levels, World Heritage sites may be destroyed by extreme climate events, and therefore, lost to future generations. Loss of cultural or natural heritage anywhere in the world is not just a loss for the country where the site is located, but for all the world’s people. This is highlighted in the 1954 ‘Convention of Aja’ for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, which states:

“… any damage to cultural property, irrespective of the people it belongs to, is a damage to the cultural heritage of all humanity, because every people contributes to the world’s culture…”.

Preserving cultural heritage means being adequately prepared to respond to the variety of threats that may compromise Authenticity, Integrity, and/or the Outstanding Universal Value of a given World Heritage Property.

UNESCO, World Heritage, and Climate Change

In 2017, UNESCO adopted a “Strategy for Action on Climate Change” (UNESCO 2017,a) to enable Member States to progress in their commitments to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change (2015) end the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. The strategy explicitly highlights that cultural heritage and cultural diversity are resources that Member States can look to and learn from in their response to climate change. The strategy explicitly highlights that cultural heritage and cultural diversity are resources that Member States can look to and learn from in their response to climate change (UNESCO 2019,b).

As such, UNESCO is involved in a variety of initiatives and projects that foster the culture-science nexus, including a joint initiative (“Evaluation of UNESCO’s Strategy for Action on Climate Change” (UNESCO 2021,c) with the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to include and promote culture as a fundamental consideration and potential resource in climate change mitigation and adaptation in IPCC assessment reports.

ICOMOS, advisory body of UNESCO, emphasizes the importance of both responding to and adequately preparing for the risks of climate change to cultural heritage and “…championing heritage as a source of resilience and an asset to climate action…” underscoring the need for better conservation and management of tangible and intangible cultural resources (ICOMOS 2019,b).

To increase engagement of cultural heritage in the wider climate discourse, the ICOMOS Climate Action Working group published the volume “The Future of our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action (ICOMOS 2019,a), which presents a multidisciplinary approach to cultural heritage intended for site managers, scientists, researchers, climate activists, and policy-makers. Considerations for this report will also influence the updating of the “UNESCO Policy Document for Climate Action on World Heritage” (described in detail below). In 2020, the ICOMOS General Assembly declared a Climate and Ecological Emergency, calling for “urgent collective action by all relevant actors to safeguard cultural and natural heritage from climate change” and to “implement heritage responses to climate change” (ICOMOS 2022).

Cultural heritage has the potential to help direct climate action and support the transition to a low carbon and climate resilient future. A better understanding of the cultural dimensions of global climate change is thus a necessary component of any climate action. Actively including cultural heritage in climate action further underlines the interconnected nature of natural and human systems. Further, raising awareness of the impacts that climate change may have on our shared cultural heritage, and all that we might lose if we do not act to the scale required, may strengthen public and political support for increased climate action. This idea threads throughout the previously mentioned ICOMOS report, stating:

“The unique power of exceptional, iconic heritage sites — including the tangible and intangible values they carry — to stir people’s souls, drive human responses and galvanise public opinion cannot be doubted” (ICOMOS 2019,a, p.2).

Cultural heritage is deeply embedded in our societies and nearly all aspects of how we view and relate to the world, and shape our individual and collective identities. Current international agreements regarding climate change require that we make bold and transformative change. In looking forward to a sustainable future that celebrates diversity and our wide mosaic of cultural identities, it is paramount that cultural heritage helps guide this transformative change.

Climate Change and UNESCO: a Brief Chronology

2005: Climate change and its impacts on World Heritage brought to the attention of the World Heritage Committee by a group of concerned organisations and individuals (UNESCO 2022).

2006: Under the guidance of the World Heritage Committee, various advisory bodies (such as ICCROM, ICOMOS, and IUCN), and a broad expert Working Group, UNESCO publishes the report “Climate Change and World Heritage. Report on Predicting and managing the impacts of climate change on World Heritage and Strategy to assist States Parties to implement appropriate management responses” (Collette 2007,a) ,alongside a “Strategy to Assist States Parties to the Convention to Implement Appropriate Management Responses“.

2007: Compilation of “Case studies” (Collette 2007,b), from selected natural and cultural World Heritage sites to illustrate the already observed and expected impacts of climate change. This leads to the adoption by the General Assembly of States Parties to the World Heritage Convention of a “Policy Document on the impacts of climate change on World Heritage Properties” (UNESCO 2008).

2016: World Heritage Committee requests the World Heritage Centre and the Advisory Bodies to periodically review and update the 2007 Policy Document with the most current knowledge and mitigation strategies available regarding climate change (UNESCO 2016, 40.COM 7 – Decision).

2017: World Heritage Committee reiterates the importance of States Parties to undertake the most ambitious implementation of the Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) by “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change”.The Committee strongly invites all States Parties to ratify the Paris Agreement and undertake actions to address climate change consistent with their obligations within the World Heritage Conventionto protect the Outstanding Universal Value of all World Heritage properties (UNESCO 2017,b, 41.COM 7 – Decision).

An international expert workshop, organised in cooperation with the UNESCO World Heritage Centre and various Advisory bodies, takes place in Vilm, Germany, to discuss climate change developements in relation to World Heritage Properties and the revision of the 2007 Policy Document.

2018: Preliminary results from the 2017’s expert workshop and recommendations for the updating of the 2007 Climate Policy Document are brought to the attention of the World Heritage Committee. Following this, the World Heritage Centre initiates the revision and updating process in close consultation with Advisory bodies, including the ICOMOS Climate Change and Heritage Working Group, and among others, senior experts in the fields of heritage conservation and management, disaster risk management, capacity-building, climate science and policy.

2019: Wide online consultation involving all World Heritage Convention stakeholders on the updating of the Policy Document launched at the end of 2019 until the end of January 2020. A questionnaire was widely circulated among States Parties, site managers, local communities, Indigenous Peoples, academics, NGOs, civil society, and advisory bodies.

2020: A first draft of the updated Policy Document was prepared by experts, incorporating policies and strategies already adopted at the international level, the overarching framework of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the periodic reporting of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the 2015 Paris Agreement, the 2015 Policy Document for the Integration of a sustainable development perspective into the processes of the World Heritage Convention, the 2017 New UNESCO Strategy for Action on Climate Change, the 2017 UNESCO Declaration of Ethical Principles in relation to Climate Change, as well as the recommendations compiled from the 2017 expert meeting in Vilm, Germany, and the outcomes from the 2019 online consultation (UNESCO 2022).

2021: Prior to the extended 44th session of the World Heritage Committee, an online meeting took place 18 June 2021 to present the draft of the Updated Policy Document on climate action for World Heritage.

Policy: Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properties

In 2005, a group of concerned individuals and organizations first raised the issue of the impacts of climate change on natural and cultural World Heritage Properties. After that, the World Heritage Committee requested (UNESCO 2005 -29 COM 7B.a Decision) the World Heritage Centre, along with Advisory bodies, interested States Parties, and petitioners, to convene an expert working group to review the nature and scale of the risks associated with climate change and to prepare a strategy and report to assist States Parties in the implementation of appropriate management responses. In this decision, the Committee encouraged States Parties to “seriously consider the potential impacts of climate change within their management planning… and to take early action in response to these potential impacts,” further noting that the “impacts of climate change are affecting many and are likely to affect many more World Heritage properties, both natural and cultural in the years to come.”

Both the report “Predicting and Managing the Effects of climate change on World Heritage” and the subsequent “Strategy to Assist States Parties to the Convention to Implement Appropriate Management Responses” (Collette 2007,a) were reviewed and endorsed by the World Heritage Committee at its 30th session (Vilnius, 2006) (UNESCO 2006 – Decision 30 COM 7.1), inviting States Parties to implement the strategy to “protect the Outstanding Universal Value, integrity and authenticity of World Heritage sites from the adverse effects of Climate Change.”

Following the report and strategy on climate change, the World Heritage Committee requested the World Heritage Centre to develop a draft policy document on the impacts of climate change on World Heritage Properties to be discussed at the General Assembly of States Parties in 2007. It was requested that the document include the following considerations:

- Synergies between conventions on the issue.

- Identification of future research needs in this area.

- Legal questions on the role of the World Heritage Convention with regard to suitable responses to climate change.

- Linkages to other UN and international bodies dealing with the issues of climate change.

- Alternative mechanisms, other than the List of World Heritage in Danger, to address concerns of international implication, such as climate change.

In 2007 the General Assembly adopted the Policy (“Policy Document on the Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properties” UNESCO 2008), strongly recommending its implementation by States Parties.

The Policy Document highlights the science and understanding of climate change available at the time of its publication, particularly highlighting the increase of Earth’s surface temperature and rising sea levels that seriously threaten Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The document further highlights that the increasing occurrence of extreme weather conditions may cause certain areas to become uninhabitable.

Also Cultural Properties are subject to a variety of threats posed by a changing climate. As evidenced in the Policy Document, climate change profoundly affects soil stability, which may in turn affect archaeological sites and remains that are highly vulnerable to any hydrological, chemical, or biological changes associated with a shift in soil stability. Another example highlights that the porous nature of historic building materials allows for greater moisture and salt mobilisation, consequently resulting in damage to decorated surfaces from salt crystallisation. It is increasingly likely that more frequent flooding episodes will damage building materials not designed to withstand prolonged immersion. The document further highlights social consequences related to climate change:

“Climate change may cause social and cultural impacts, with communities changing the way they live, work, worship and socialise in building sites and landscapes, possibly migrating and abandoning their built heritage. Climate change may also cause impacts on livelihoods, food security, and the social fabric as a whole.” (UNESCO 2008, p.3).

The Document responds explicitly to what was requested by the General Assembly of States Parties:

Synergies with other international conventions and organisations

At the global level, the World Heritage Centre and Advisory Bodies seek to enhance synergies and foster cooperation between relevant organisations and structures working on climate change through networking for research, knowledge sharing, exchange of best practices, education and training, awareness raising and capacity building.

The comparative advantage of the World Heritage Convention and the impact it may have on climate change mitigation, relies on the States Parties’ obligations to protect the Outstanding Universal Value of their Heritage Properties. Actions taken to mitigate the impacts of climate change at such well-known sites may influence the adoption of good management practices elsewhere. The overall objective to safeguard the OUV of World Heritage Properties allows these sites to “serve as laboratories where monitoring, mitigation and adaptation processes can be applied, tested and improved.”

States Parties to the Convention and managers of World Heritage properties are simultaneously encouraged to undertake site-level monitoring, mitigation, and adaptation measures and, where appropriate, include climate change communication, education, and activities to improve public awareness and knowledge of climate change and its potential to impact World Heritage Properties and their values.

Research needs

The document highlights the need for increased data relevant to how climate change will impact various World Heritage Properties, particularly in regard to cultural ones. It further describes the need for increased capacity and financial resources for research, especially in developing countries, to more fully understand the current and predicted impacts to heritage. Site-specific research at World Heritage Properties helps raise public awareness regarding the dangers of climate change, and therefore, has the potential to help increase public and political support for concrete climate action.

The document identifies three different research needs:

- Research that responds to increased risk factors such as fire, drought, floods, avalanches, glacial lake outbursts, to support disaster management plans for properties.

- Socio-economic research, such as cost-benefit analysis, evaluation of the economic losses from climate change and contingent assessment, as well as research into the impacts of climate change on societies, particularly traditional ones or in sites such as cultural landscapes where the way of life contributes to the OUV.

- Research into the natural and sources of other stress factors (e.g. pollution, sedimentation, deforestation, poaching) impacting on properties, which can greatly reduce their resilience to the impacts of climate change.

Legal questions and alternative mechanisms

Articles 4 and 5 of the Convention highlight the fundamental obligation of States Parties to protect and conserve World Heritage Properties:

“Each State Party to this Convention recognizes that the duty of ensuring the identification, protection, conservation, preservation and transmission to future generations of the cultural and natural heritage … situated on its territory, belongs primarily to that State. It will do all it can to this end, to the utmost of its own resources and, where appropriate, with any international assistance and cooperation, in particular, financial, artistic, scientific and technical, which it may be able to obtain.[…]”. (UNESCO 2008, p.6).

This provision is the basis for States to ensure they are doing all that is necessary to address the causes and impacts of climate change on World Heritage Properties situated on their territories.

In the context of climate change, Article 6 of the Convention highlights the need for international collaboration to assess and address the causes and impacts of climate change on World Heritage Properties:

“…the States Parties to this Convention recognize that [such heritage] constitutes a world heritage for whose protection it is the duty of the international community as a whole to cooperate… States Parties [must] not take any deliberate measures which might damage directly or indirectly the cultural and natural heritage.” (UNESCO 2008, p.7).

Revisions to the Convention’s Operational Guidelines

The Operational Guidelines (UNESCO 2021,a) are the main instrument for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention.

Periodically updated, the most recent 2021 Operational Guidelines highlight climate change in several points, including the recommendation for States Parties to include disaster, climate change and other risk preparedness as an element in their World Heritage site management plans and training strategies. The Operational Guidelines ensure the “long-term safeguarding of Outstanding Universal Value and the strengthening of heritage resilience to disasters and climate change.”

Conclusions of the 2007 Policy Document

The World Heritage community will work in collaboration with other partners and organisations, understanding shared responsibility, resources, and expertise in addressing the impacts of climate change on the Outstanding Universal Value, Authenticity, and Integrity of World Heritage Properties. The World Heritage Committee stands as an advocate for climate change research and properties are used where appropriate as a means to raise awareness about the various impacts this issue has on World Heritage. As such, climate change should be considered in all aspects of nominations, managing, monitoring and reporting on the status of World Heritage Properties. The Policy Document recognizes climate change as an existing and evolving threat to the OUV, Authenticity, and Integrity of World Heritage, and as such, the Committee recognises the utility of existing tools (e.g. List of World Heritage in Danger) and various processes (e.g. Reactive Monitoring, Periodic Reporting) of the Convention and the Operational Guidelines.

Research Priorities of the 2007 Policy Document

● Understanding how a changing climate impacts the vulnerability of indoor, outdoor and buried material (such as the impacts posed by a dramatic increase or decrease in moisture).

● Understanding how traditional materials and practices can adapt to a changing climate and extreme weather events.

● Development of methods and technologies for monitoring of site-specific climate impacts.

● Understanding how climate change impacts people and society, such as the movement of peoples, displacement of communities, their practices, livelihoods, and their relation with their heritage.

New Strategies after the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda

The updated “Policy Document on Climate Action for World Heritage” was endorsed by the World Heritage Committee at its extended 44th session (online on 2021; UNESCO 2021,b – Decision 44 COM 7C), however it was requested that the UNESCO World Heritage Centre and Advisory bodies revise the updated document by incorporating amendments submitted during the extended 44th session, and to consult with World Heritage Committee members regarding the following (UNESCO 2022):

- The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC) of States Parties, which is a fundamental pillar of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

- The alignment of climate change mitigation actions with CBDR-RC and the Nationally Determined Contributions accepted under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, except on a voluntary basis.

- The need for support and capacity-building assistance, as well as the encouragement of technology transfer and financing from developed to developing countries.

Taking into consideration both the October 27, 2021 draft “Updating of the Policy Document on climate action for World Heritage” (UNESCO 2021,e) and the various comments added by States Parties, the General Assembly of States Parties established an open-ended Working Group of States Parties, assisted by the World Heritage Centre and Advisory bodies, to develop the final version of the updated climate Policy Document to be presented in 2023 (UNESCO 2022).

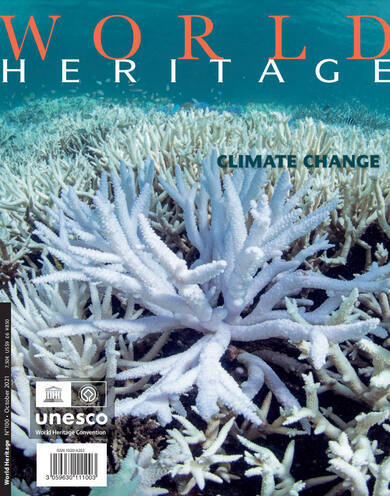

The science regarding climate change has become increasingly abundant and clear. Anthropogenic climate change has led to unprecedented concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases, resulting in approximately 1°C of global warming above pre-industrial times. This warming causes long-term changes in the global climate system, resulting in variation in the dynamics of rain patterns, sea-level rise, ocean warming and acidification, as well as an increased intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, storms, fires, floods, and droughts, with some impacts “long-lasting or irreversible”.

“Climate change has become one of the most significant threats to World Heritage, impacting the Outstanding Universal Values (OUV), including integrity and authenticity, of many properties, as well as the economic and social development and quality of life of communities connected with World Heritage properties.“(UNESCO 2021,e, pp.16)

The updated policy document aims to address a number of key challenges and gaps in the implementation of the 2007 version. The document takes into account already adopted international policies and strategies, such as the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the regular reporting by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Paris Agreement (2015), the Policy Document for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention (2015), the New UNESCO Strategy for Action on Climate Change (2017), and the UNESCO Declaration of Ethical Principles in relation to Climate Change (2017).

The document further highlights the interconnections between climate change and its impacts on cultural World Heritage Properties. Cultural landscapes, historic cities, archaeological sites, and vernacular architecture are impacted by climate change, while also demonstrating locally developed strategies for climate change mitigation through “energy efficient built form and sustainable use of local resources” (UNESCO 2021,e, p. 17). The document further highlights the interconnections between climate change and its impacts on cultural World Heritage properties. Cultural landscapes, historic cities, archaeological sites, and vernacular architecture are impacted by climate change, while also demonstrating locally developed strategies for climate change mitigation through “energy efficient built form and sustainable use of local resources”(UNESCO 2021,e, p. 18).

“…World Heritage properties can play an exemplary role in implementing integrated approaches that link both cultural and natural heritage in climate action and demonstrate how transformative change can help in strengthening resilience and achieving sustainable development.” (UNESCO 2021,e, pp. 21).

World Heritage Climate Action Goals

The updated document presents a set of climate action goals looking towards 2030. These goals “guide how World Heritage processes can effectively contribute to the transformative change needed to halt and reverse the negative trends associated with climate change.” The proposed goals, and key categories of climate action regarding World Heritage Properties, include assessing climate risks, climate adaptation, climate mitigation, knowledge sharing, as well as capacity and awareness building.

The Updating Process of the Policy Document: Recommendations and Guiding Principles

● Ensuring the updated document is fully anchored in the World Heritage system, within the scope of the Convention.

● Establishing clear links with the UN 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement, and all other relevant World Heritage policies.

● Grounding it in contemporary climate policy and the best available science, while also recognizing the importance of Indigenous knowledge systems for the management and conservation of World Heritage Properties

● Highlighting the importance of education and capacity-building

● Having an action-oriented approach, clearly identifying the actors, their roles, and responsibilities (Committee-level, national-level, site-level)

● Finding the balance between a too general approach and one which would be too prescriptive

● Ensuring sufficient guidance to encourage and facilitate its implementation at all levels

The main gaps in the 2007 Policy Document addressed by the updated document:

● The 2007 policy functions as an international tool for climate change but does not provide adequate guidance for its implementation

● Does not recognize the direct or indirect impacts of climate change on communities and intangible heritage of World Heritage Properties

● Missing guidance for adaptive management

● Practical recommendations and guidelines to mitigate climate change on properties to be incorporated

● Need for increased awareness of the document and its implications at the national, local, and property levels

Key Recommendations for the updated document:

● A thematic approach with respect to various climate change hazards and different typologies of heritage

● Consider vulnerability of Intangible Heritage to the impacts of climate change

● Reflect the interconnectedness between nature and culture

● Emphasise the risk assessment of World Heritage Properties due to climate change, particularly with impacts to OUV

● Develop and update baseline data for assessing the impact of climate change on Heritage Properties

● Encourage States Parties to actively participate in monitoring, adapting, mitigating, and responding to climate change impacts.

Guiding Principles:

The updated policy includes a number of guiding principles to accompany its implementation:

1. Adopt a precautionary approach aimed at minimising the risks associated with climate change

2. Anticipate, avoid and minimise harm to protect the heritage of Outstanding Universal Value

3. Use best available knowledge, generated through disciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary processes, including from scientists, researchers, site managers, Indigenous Peoples and local communities

4. Integrate a Sustainable Development Perspective

5. Promote global partnership, inclusion and solidarity

The long-term vision of this policy document is that each State Party understands the current and future impacts that climate change may have on the Outstanding Universal Value of a given World Heritage Site, and undertakes “effective, ambitious, cooperative and active” climate action.

Climate Change and Historic Cities

Dominant western narrative tends to uphold that climate change is a problem of the future. However the message of the 2022 IPCC report is clear: if we want to mitigate the worst effects of climate change, we need to act now. Extreme weather events have already impacted various areas around the world, threatening livelihoods and presenting a threat to many cultural landscapes and World Heritage properties. In 2007, following the UNESCO report on “Predicting and Managing the Effects of Climate Change on World Heritage” (Collette 2007,a), a compilation of “Case Studies” (Collette 2007,b) on Climate Change and World Heritage was prepared under the guidance of the World Heritage Committee.

Perhaps one of the most evident examples of climate change threatening cultural heritage is Venice and its Lagoon.

Rising waters and flooding are becoming increasingly frequent events for the city of Venice and conservative modelling suggests that Venice could be flooded daily by the end of the century.

Like many historical cities, Venice not only faces the threat of climate change but also the pressures of over-tourism, large cruise ships, and new developments. In 2019, the World Heritage Committee warned that significant progress, as well as an integrated management system, would be necessary to keep the city off the List of World Heritage in Danger. Following the recommendation of the World Heritage Committee, the Italian government banned large cruise ships from entering the Venice Lagoon starting from 2021. Although the property is not currently listed as endangered, many factors still threaten the characteristics that define it as a World Heritage Property of Outstanding Universal Value, including the constant decrease of population and the lack of an integrated management plan to safeguard the city’s historical authenticity.

According to UNESCO, more than one-third of World Heritage cities are located in coastal areas threatened by rising sea levels (UNESCO 2021,f). Although this represents a large-scale and very noticeable threat, climate change is also impacting Heritage Properties that do not face the looming danger of rising tides. Higher temperatures, increased precipitation, drought, and the increased frequency of extreme weather events threaten a number of Heritage Sites and the economies and communities that depend on tourism. As outlined in the UNESCO report “World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate” (UNEP/UNESCO/UCS 2016), the threats of climate change have the potential to seriously degrade the “very attributes that make World Heritage sites such popular tourist destinations,” as well as exacerbating other stresses including pollution, rapid urbanisation, loss of intangible cultural heritage and the impacts of poorly managed tourism. Although providing wonderful opportunities to learn and experience the world, tourism is heavily reliant on energy-intensive modes of transport and is estimated to contribute approximately 5% of global carbon emissions (UNEP/UNESCO/UCS 2016). It should be additionally noted that 70% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions are produced by cities, and as such, they must play an important role in climate mitigation and adaptation (UNESCO 2021,f). A key aspect of confronting the climate crisis in World Heritage Cities and ensuring adequate urban heritage conservation is underscored in the variety of programs, initiatives, and international agreements regarding sustainable development. UNESCO promotes the implementation of sustainable tourism and measures to reduce the impacts of climate change to increase the resilience of World Heritage.

“Continued climate-driven degradation and disruption to cultural and natural heritage at World Heritage sites will negatively affect the tourism sector, reduce the attractiveness of destinations and lessen economic opportunities for local communities.” (UNEP/UNESCO/UCS 2016)

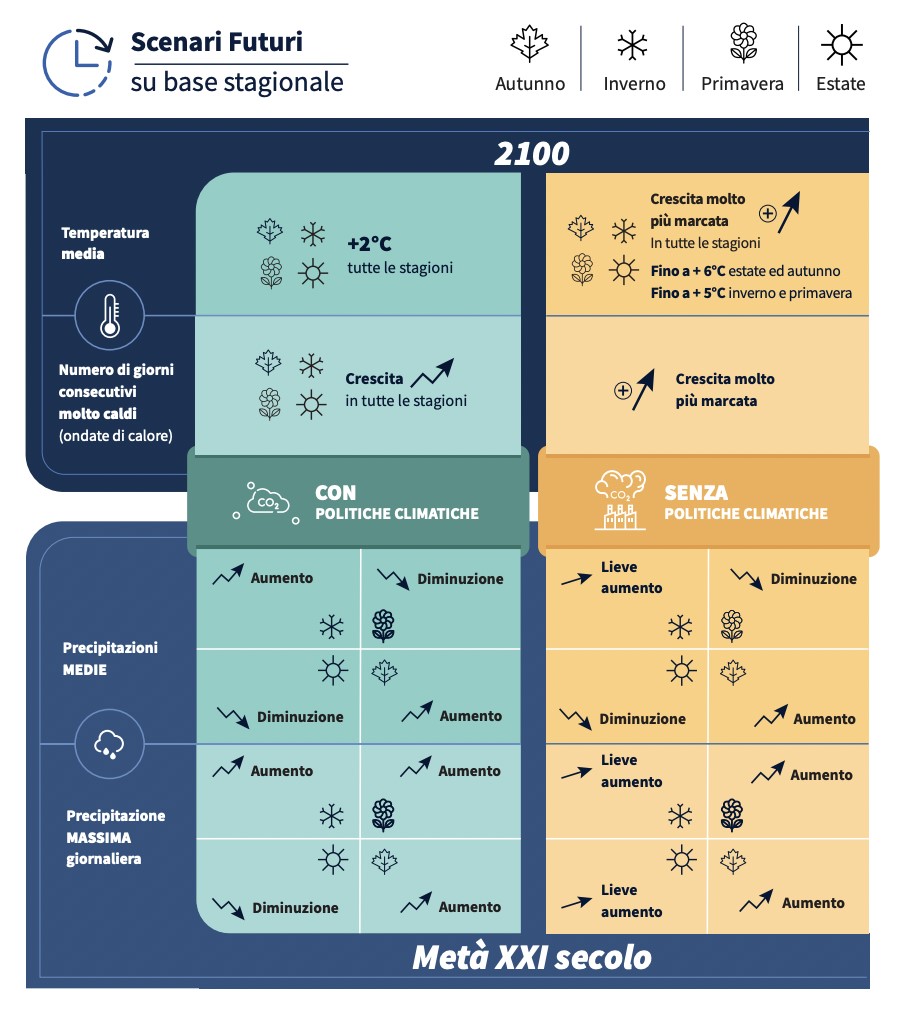

In the last decade, Rome has experienced a record number of extreme weather events, including flooding after intense rainfall, tornadoes, and prolonged droughts connected to extreme temperature. These events interrupted public transport, damaged infrastructure, and brought various risks to public health and safety. An analysis of the risks connected to climate change, by the Centro Euro-Mediterraneo sui Cambiamenti Climatici (CMCC), highlights the various risks facing Rome, including the increasing trends of average temperature, hot nights, and maximum daily precipitation. As highlighted in the document edited by the CMCC (Spano et alii, 2021), each year since 2011, has recorded higher temperatures compared to the year before, which profoundly impacts human health and energy:

This analysis shows that, without adequate climate policy, Rome should expect an increase in average temperature in all seasons, coupled with a decrease in average precipitation during summer months:

As outlined in the CMCC report, the two most significant factors relative to climate change in Rome are temperature and precipitation. Urban environments heat up more than surrounding areas and are thus defined as urban heat islands. The city of Rome, like other big cities, is densely constructed and subjected to high levels of pollution (further aggravated by the increased use of air-conditioning). As predicted by the analysis, an increase in the duration of heatwaves will result in a marked increase in associated daily mortality.

With respect to precipitation, Rome is particularly exposed to pluvial (i.e. rainfall) and fluvial (river) flooding. Since approximately 91% of Rome’s urban territory is impervious, stormwater disposal is difficult and tends to damage built structures. From 2010 to 2020, there were roughly 42 intense precipitation events in Rome. As already noted, climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of flooding events, placing both civilians and Rome’s rich collection of cultural heritage. There is a regulatory framework regarding current and future risks posed by climate change to the city, including the Strategia di Resilienza (100 Resilient Cities), the Patto dei Sindaci per il clima e l’energia and the global network C40, which are all aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and environmental risks, while also encouraging sustainable and resilient cities. It would be desirable to explicitly add the risk factors, and possible solutions, regarding the climate change impacts on the city’s built World Heritage.

Atmospheric Pollution puts Cultural Heritage at Risk

Bibliografy and Sitegrafy

- CMCC. Centro Euro-Mediterraneo sui Cambiamenti Climatici, “Analisi del Rischio, I cambiamenti climatici in sei città italiane“, ROMA”. 2021: https://www.cmcc.it/it/rischio-clima-citta-2021

- Collette A. (ed.), “Climate Change and World Heritage. Report on Predicting and managing the impacts of climate change on World Heritage and Strategy to assist States Parties to implement appropriate management responses”. UNESCO. France, May 2007a: https://whc.unesco.org/documents/publi_wh_papers_22_en.pdf

- Collette A. (ed.), “Case Studies on Climate Change and World Heritage”. UNESCO. France, 2007b: https://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/473/

- ICOMOS. Climate Change and Cultural Heritage Working Group, “The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging cultural heritage in climate action”. Paris, 1 Jul 2019a: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2459/1/CCHWG_final_print.pdf

- ICOMOS, “ICOMOS work on Climate change”. 13 Sept. 2019b: https://www.icomos.org/en/focus/climate-change/60669-icomos-work-on-climate-change

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS Working Groups, “Climate Action Working Group”. 23 Mar. 2022: https://www.icomos.org/en/what-we-do/disseminating-knowledge/icomos-working-groups?start=6

- MiC. Ufficio UNESCO, “ Convenzione dell’Aja; La Convenzione per la protezione di beni culturali in caso di conflitto armato (1954) e protocolli aggiuntivi”: https://www.unesco.beniculturali.it/english-convenzione-dellaja-1954/

- MiC. News: “UNESCO, evitata l’iscrizione di Venezia nella lista del patrimonio mondiale in pericolo”. 22 Lug. 2021: https://www.beniculturali.it/comunicato/21014

- Pörtner H.-O. et alii (eds.), “IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability”, in Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. In Press. 2022: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

- Spano D. et alii, “Analisi del rischio. I cambiamenti climatici in sei città italiane” . Centro Euro-Mediterraneo sui Cambiamenti Climatici. 2021: https://files.cmcc.it/rischio_clima_2021/CLIMA_Roma_Completo.pdf

- UNECE, “Air pollution puts cultural heritage at risk”. 13 Mar. 2015: https://unece.org/environment/news/air-pollution-puts-cultural-heritage-risk

- UNECE, “Dirty air endangers UNESCO World Heritage Sites and produces high costs”. 10 Maj 2020: https://unece.org/media/Environment/press/1414

- UNEP/UNESCO/UCS, “World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate”. Kenya, France, USA, 2016: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tourism-climate-change/

- UNESCO, “Convenzione riguardante la protezione sul piano mondiale del patrimonio culturale e naturale”. France, 1972: https://www.unesco.beniculturali.it/pdf/ConvenzionePatrimonioMondiale1972-ITA.pdf

- UNESCO, “Decision 29 COM 7B.a Threats to World Heritage Properties”. 29th Session of the World Heritage Committee (29 COM), 2005: https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/351/

- UNESCO, “Decision 30 COM 7.1 Iussues Related to the State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties: the Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properites ”. 30th Session of the World Heritage Committee (30 COM), 2006: https://whc.unesco.org/en/CC-policy-document/

- UNESCO, “Policy Document on the Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properties”. Paris, 2008: https://whc.unesco.org/en/CC-policy-document/

- UNESCO, “Decision 40 COM 7 State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties”. 40th Session of the World Heritage Committee (40 COM), 2016 : https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/6817/

- UNESCO, “UNESCO Strategy for Action on Climate Change”. Item 4.9 of the provisional agenda. 39th Session General Conference. Paris, 2 Oct. 2017,a: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259255

- UNESCO, “Decision 41 COM 7 State of Conservation of the Properties Inscribed on the World Heritage List”. 41st Session of the World Heritage Committee (41 COM), 2017,b: https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/6940/

- UNESCO, “UNESCO closely monitoring ongoing threats to Venice World Heritage site”. 14 Oct. 2019,a: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2043/

- UNESCO, “Changing minds, not the climate: UNESCO mobilizes to address the climate crisis”. Paris, 2019,b: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370750.locale=en

- UNESCO, “Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention”. World Heritage Centre. Paris, 3 Jul. 2021,a: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/

- UNESCO, “Decision 44 COM 7C Amended draft decision”. Extended 44th Session of the World Heritage Committee 18 July 2021,b: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/188493

- UNESCO, “Evaluation of UNESCO’s Strategy for Action on Climate Change”. (2018 – 2021), IOS/EVS/PI 196. Paris, May 2021,c: https://whc.unesco.org/en/sessions/44COM/documents/

- UNESCO, Internal Oversight Service, “Evaluation of UNESCO’s Strategy for Action on Climate Change”. Item 8 of the provisional agenda. 212 Session Executive Board, Paris, 16 Aug. 2021,d: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378552_eng

- UNESCO, “Updating of the Policy Document on climate action for World Heritage”. 23rd Session of the General Assembly of States Parties. Paris, Nov. 2021,e: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2021/whc21-23GA-inf11-en.pdf

- UNESCO. Events: “World Heritage City Lab — Historic Cities, Climate Change, Water, and Energy”. 16-17 Dec. 2021,f: https://whc.unesco.org/en/events/1633/

- UNESCO. News: “Venice and its Lagoon”. 2021,g: https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/4102/

- UNESCO, “Climate Change and World Heritage”. 2022: https://whc.unesco.org/en/climatechange/

Kristen Pundyk