At the beginning of the new millennium, within the Earth Sciences, the term Anthropocene was coined to indicate a geological phase in which, at the end of the Holocene, the following period is characterized by the absolute prevalence of Man as formative agent of the dynamics of transformation of the Earth.

Anthropocene: what is it?

The term Anthropocene was coined at the beginning of the new millennium, within the Earth Sciences.

It points out a geological phase in which, at the end of the Holocene, the following period is characterized by the absolute prevalence of Man as the formative agent of the dynamics of transformation of the Earth.

Paul Crutzen, a Dutch engineer and meteorologist, Nobel Prize for chemistry, who died in 2021 at the age of 87, was among the first to talk about Anthropocene, launching a term destined to crystallize in the lexicon of many disciplines, scientific and not.

The definition process: approval and definition of chronological unit

The accumulation/erosion/transformation macro-processes (chemical and physical) of our Planet, that had been almost absolute prerogative of Nature until the Industrial Revolution, have undergone a progressive change of course, leading to an exponential responsibility of human actions on the direct change of physical, chemical and biological parameters in geological deposits.

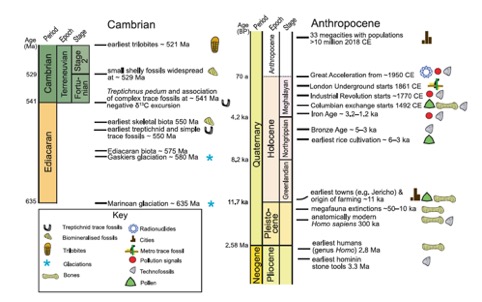

The phenomenon has been even more evident as a result of industrial globalisation, leading the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (in short AWG Group) of the ICS (International Commission on Stratigraphy), to set up, in 2009, a specific working group to deepen the theme of the Anthropocene, considering the possibility of including it in the Geological Chronological Scale as an era, after the Holocene. (Working Group on Anthropocene).

Following a detailed reflection, which lasted almost ten years, on May 21st 2019, the Working Group voted a resolution in which it responds in the affirmative to the question whether the Anthropocene can be considered a specific chrono-unitstratigraphic, whose revealing signals can be clearly identified from the middle of the 20th century.

The discussion about the adoption of the term Anthropocene as chronostratigraphic unit recognized in the seriation of the Quaternary is still open, as its official adoption will have to be ratified by the Executive Commission of the IUGS (Executive Committee of the International Union of Geological Sciences).

However, all the necessary bases to make a new reflection, at a global level, on the meaning of the presence of Man on Earth, have already been laid.

The most recent statement of the scientific community involved in the process of defining the Anthropocene in chronostratigraphic terms tends to move forward the term of the beginning of the periodization, placing it in a phase (mid-twentieth century) defined as “Great Acceleration”.

However, in the intentions of the first scientists who spoke of Anthropocene, we can clearly see a broader vision, which closely relapsed specific human actions to climate change and, more generally, to the history of the planet, from a much earlier stage:

“In proposing this new term, Crutzen and Stoermer (…) indicated the onset of the Anthropocene as “the latter part of the 18th century … when data retrieved from glacial ice cores show the beginning of a growth in the atmospheric concentrations of several ‘greenhouse gases’, in particular CO2 and CH4.” They, and Crutzen (…), linked this physical record with the global effects of human activities associated with the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the UK, catalyzed by the development of a greatly improved steam engine by James Watt.”

(Waters C.N. et alii 2021, p. 2)

Since this reflection on the processes of transformation of the Planet involves fields and levels of human action on a large scale, the term Anthropocene is de facto enlarged, going beyond Earth Sciences and involving aspects of sustainability and environmental ethics, socio-anthropology and, more generally, humanities and social sciences: scholars of the most varied disciplines wonder not only about the presuppositions of such a definition, but above all about the consequences of this uncontrolled anthropization, in a debate that cannot be lacking in a holistic and global approach.

Holocene

The Holocene is the second epoch of the Quaternary period. Its name comes from the Greek ὅλος (holos, totally, absolutely) and καινός (kainos, recent).

The period follows the Würm Glaciation (also known as the Baltic-Scandinavian glaciation or Weichselian glaciation) and is characterized by the remarkable fluctuations of the climatic phases that have contributed to its subdivision into five chronozones:

Preboreal (ca. 10,000 – 9000 B.C.)

Boreal (ca. 9000 – 7000 B.C.)

Atlantic (ca. 7000 – 3,700 B.C.)

Subboreal (ca. 3,700 – 450 B.C.)

Subatlantic (450 B.C. – present)

Modern human civilization is dated entirely within the Holocene; this is still valid until the IUGS (v. above) will definitively approve the existence of the new Anthropocene era.

The Blytt-Sernander classification of climatic periods, initially defined on the basis of moss residues of the genus Sphagnum, is now purely of historical interest. The scheme was defined for Northern Europe, however assuming that climate change applied to all areas. The periods of the scheme include some final oscillations of the last pre-Olocenic glacial period and then classifies the climates of the most recent prehistory.

To be more recent distinguishes Holocene from the previous periods (e.g. the Pleistocene) also for the impossibility on the part of palaeontologists to determine downright faunal stages for the Holocene, due to the great detail available for different geographic areas: when subdivision is necessary, periods of development are usually used. However, the periods of time to which these terms refer vary depending on the different appearance of those technologies in different parts of the world.

Anthropocene as consciousness: to thrill not to amaze but to make it part

As for all the ages that preceded it, the definition of Anthropocene in geostratigraphic field is based on “isosynchronicity”, that is on phenomena, documentable and verifiable on all the Planet, in the arc of the same time.

But since its first appearance, Anthropocene configures itself as “The Age of Man”, and in this enlarged vision, characterized as “diachronic” and “trans-temporal”: it varies regionally, ever since Homo Sapiens has gained the ability to change the ecology of the Planet as no other species has ever been able to do.

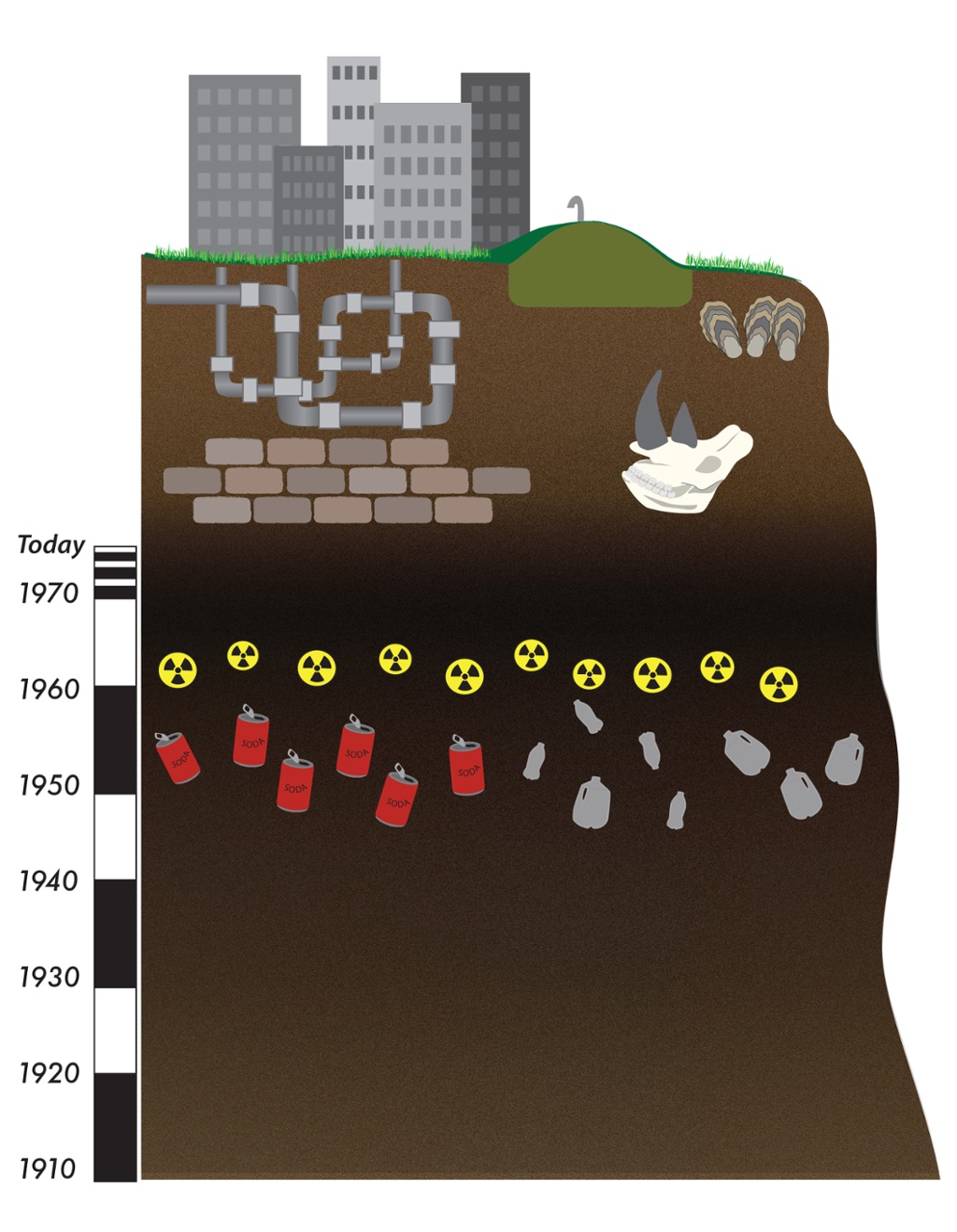

Despite this peculiar “space-time” scale, the “Great Acceleration”, as it has been defined, has produced clearly visible traces of this “high human impact” such as to configure significant, long-lasting and vast phenomena of change in the Earth’s ecosystem, well visible and documentable today.

The Exhibition

Often this rapid and exponential change of paradigm has led to replace reflection with instinctiveness, analysis with such an extreme synthesis, not infrequently preferring a hasty to a synthetic information, replacing a superficial knowledge to critical learning.

But, whatever they are, “mass media” are just mediators between our mind, our logical capacity, and the emotional world.

It is therefore possible also through the use of images to reach a deep awareness of tangible facts and phenomena, using their expressive power to get to touch and vibrate the deepest emotional strings.

Is this the instrument that has known very effectively to engage the exhibition Anthropocene, curated by Urs Stahel, Sophie Hackett and Andrea Kunard and organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Canadian Photography Institute of the National Gallery of Canada in partnership with the MAST Foundation in Bologna.

Using as a means of expression almost exclusively the “vision”, it has transformed the images in growth of consciousness, allowing viewers, including many schoolchildren and young people, to really understand the extent of the Anthropocene phenomenon.

Browse the catalogue of the exhibition

Anthropocene in the literature

Already in the late 80s of the last century, the definition coined by science fiction writer K. W. Jeter and especially after the release of the well-known novel by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling “The Difference Engine” (1990), followed by films directed by filmmaker such as Terry Gilliam, Antony Lucas, Luc Besson and especially Tim Burton, a current called Steampunk has brought to the fore the “steam revolution”, revisited in a sci-fi dreamy version.

And so it comes to create a strange marriage, between Steampunk and Anthropocene precisely. It emphasizes that, beyond the learned scientific disquisitions that still try to define a chronostratigraphic term for the beginning of this new era, in the imagination of the younger generations industrialization, since its beginnings, held clearly “in nuce” the germ of what would inevitably happen from there to a handful of decades (…a trifle in geological terms!)

Nature and Culture: the care of what is produced by Man is no longer separable from the care of the Planet

As the concept of Anthropocene expands among the international scientific community, the focus of the discussion is shifting from a model of progressive transgression between Holocene and Anthropocene, to a clear and rapid transition of the conditions of the Earth System.

Attention must be paid to the fact that the Anthropocene, in its chronostratigraphic/geochronological sense, includes all the events and processes that occurred, in its time span, on Earth, regardless of whether they are anthropic (i.e. caused by man) or natural.

Therefore, the historical contrast between nature and culture, so dear to the debate that arose in the 70s and 80s of the last century in the archaeological and social sciences, seems to lose definitively its sense: the man’s history and natural history are now indissolubly merged into a single History (Chakrabarty, 2009; Hamilton, 2017), or perhaps better, the “animal man” has now become aware that he has never really gone out of the Wild.

In this regard it should be noted that the concept of “Anthropocene” differs sharply from the concept of anthropocentrism.

In depicting the extent of the changes (in the geosphere, in the biosphere, etc.) that Man is able to make with respect to any other living species, in our planet or outside it, disposing in an unlimited and indiscriminate way of what nature can offer, we do not put Man’s action at the centre of the Universe (Haraway, 2016; Tsing, 2012; Horn & Bergthaller, 2020).

On the contrary, Anthropocene, in the broadest and multidisciplinary sense of the term, represents the awareness of the deep interrelation that exists throughout the Universe, Sapiens sapiens species included, and especially the extent of the dangers that the systematic alteration of this balance is actually bringing to the entire system of life on Earth.

In this wide-ranging debate, Historians, Archaeologists, Sociologists, Philosophers, though with due interpretative differences, are at ease. But International Law, but even more so Economics, are among the disciplines that are most difficult to relate to this new concept of the geological era, creating an important fracture within a global, diachronic and long-term vision.

Relevance of Anthropocene in International Law and Economics

Relevance of Anthropocene essentially from two points of view: to investigate which are the most “sensitive” legislative areas, able to influence the forces of most push towards a strong human impact on territories (i.e. laws of the sea, land law, etc.) and, even more complex issue, how international laws can protect against the consequences of such an impact, while remaining relevant in regulating relations between states.

In this case, the rapid approval of a strict geo-stratigraphic definition of the term is fundamental to ensure that Anthropocene becomes an “incontrovertible fact”, universally accepted, not open to interpretations, suitable for supporting precise international standards recognised by States.

The picture is well outlined by Waters et alii 2021:

“For international law scholarship, two links to the Anthropocene have emerged. First, how core parts of international law, such as of the law of the sea but also of territory and its acquisition over centuries, facilitated the emergence of forces that led to ever-greater human impacts on the Earth System (Vidas, 2011; Viñuales, 2018). Second, how international law can evolve to be able to embrace the consequences of changes in the Earth System and remain relevant for the regulation of interstate relations (e.g., International Law Association [ILA], 2018). International law discussion concerning the Anthropocene is, however, less about its conceptual content and more about the consequences of the geological, Earth System change that it represents. This means that international law will largely rely on the geological interpretation of the Anthropocene, should it be formalized. Indeed, upon being formally adopted through a rigorous procedure within the competent geological/chronostratigraphic bodies, the scientific fact of the Anthropocene as a new epoch will become considered a fact of common knowledge—a “notorious fact,” with a legal implication of not being open to interpretation, but rather providing an inherent part of the overall context within which international law operates.”

Economic theories, even when dealing with aspects of nature, such as raw materials, tend to treat them “separately” from their context, as elements subject to “market laws”.

It is not by chance that a famous political economist, Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832) identified the public goods, as “the air we breathe”, as totally irrelevant from the economic point of view, as not saleable nor affordable.

It is evident that this attitude leads to ignore the concept of Anthropocene, when not to enter directly into conflict with it, as Economy is the main sector involved in the causes of the “Great Impact”.

The only exceptions, at the moment very restricted, those sectors of alternative economic disciplines directly interested in the “ethical” aspects of ecology and sustainability of population growth.

Anthropocene and Cultural Heritage

Anthropocene and Cultural Heritage and Anthropocene is excellently summed up by the words of Antonio Lucci, scholar and researcher of Aesthetics of History at the Humbold Un. of Berlin:

“Anthropocene’s central question concerns rethinking the relation between humans and the environment, their interactions, interconnections and interdependence. For this reason, issues of conservation, evaluation and valorization of the human works inserted in the environment are key

issues within Anthropocene. In this sense, cultural heritage is to be considered essential in the mediation between nature and humans, as the permanent trace of the relation between humans and the world as a whole.

The permanence and conservation of human artifacts after the disappearance of the generations that have produced them, opens up the issue of the cultural legacy, in terms of what people from our generation intend to bequeath to future generations, as well as recognizing what the past generations have passed on to us. Artworks, buildings, human constructions, as well as ideas, techniques and forms of organization that have changed the Earth to make it inhabitable, are central issues for a philosophy wishing to address the present epoch.” (Lucci A. 2018)

In 2010, as part of the important international exhibition “dOCUMENTA” held every five years in Kassel, (Germany), artist Amy Balkin, a well-known exponent of ecological themes in the artistic field, launched the initiative to include Earth’s atmosphere in the World Heritage List. Her proposal was detailed and well-motivated: it was based on the assumption that the state of emergency in which the health of our Earth atmosphere is found was in perfect harmony with the assumptions and aims of UNESCO and that there was an undeniable universal interest for what can be considered by definition a “common good”.

This “World Heritage Site” would have transcended all boundaries, extending from sea level to the “Kármán Belt”, at a height of 100 Km above sea level, where the limit between the Earth’s atmosphere and cosmic space is set.

Soon the artist had to face various problems: the request had to be submitted by a State, or by a partnership of States. Kassel sent invitations to 186 countries, but there were no accessions.

The German Federal Ministry did not consider it appropriate to submit the application, even after having received over 90,000 postcards that responded to the artist’s appeal.

The priority of the protection of a universal good such as the air we breathe, we together with all living beings on the planet, clashed in the face of obvious political, economic, transnational interests and the impossibility for humanity to reason “out of bounds”.

We have seen how the main definition of Anthropocene, in its essential geo-chronostratigraphic meaning, is based on the possibility of identifying precise indicators of a set of global phenomena, which go beyond the geographical limits of territories and nations, and that are synchronic, over the long – very long period.

The two cases above show us that the theme of the protection of the Universal Cultural Heritage indicates the same key to understanding: that we must go beyond geopolitical limits in defining the value of heritage and to transmit its memory through generations.

Anthropocene and UNESCO

Biocapacity

This concept was first put forward in the early 1990s by the Swiss sustainability advocate, Mathis Wackernagel, and Canadian ecologist William Rees. Their research on the biological capacity of the planet required by a given human activity, led them to define two indicators: biocapacity and the ecological footprint (see below). Since 2003, these two indicators have been calculated and developed by the Global Footprint Network, which defines biocapacity as “the ecosystems’ capacity to produce biological materials used by people and to absorb waste material generated by humans, under current management schemes and extraction technologies”.

Capitalocene

This term was put forward by American environmental historian and historical geographer Jason W. Moore, who preferred to use the term Capitalocene rather than Anthropocene. According to him, it is capitalism that has created the global ecological crisis leading us to a change of geological era. A variant of the Capitalocene, the notion of Occidentalocene, affirmed notably by the French historian Christophe Bonneuil, holds that responsibility for climate change lies with industrialized Western nations and not the poorest countries.

Co-evolution of genes and culture

According to American sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson, genes have made possible the emergence of the human mind and human culture (language, kinship, religion, etc.) and, conversely, cultural traits could favour genetic evolution in return. This happens through the stabilization of certain genes that give a selective advantage to members of the group in which the cultural behaviour is observed. Several anthropologists and biologists have criticized this idea of “co-evolution” between genes and culture, arguing that the transmission of cultural traits is a volatile phenomenon that does not obey the laws of Darwinian evolution. They also argue that, over the past 50,000 years, humankind has experienced significant cultural transformations, whereas the human gene pool has remained unaltered (with only a few exceptions).

Ecological footprint

According to the Global Footprint Network, this term is “a measure of how much area of biologically productive land and water an individual, population or activity requires to produce all the resources it consumes and to absorb the waste it generates, using prevailing technology and resource management practices”.

Geological epoch

The geological timescale is characterized by different kinds of time units – eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages. To be recognized as such, each subdivision must have palaeo-environmental (climatic features), palaeontological (fossil types) and sedimentological (resulting from erosion by living beings, soils, rocks, alluvion, etc.) conditions, that are similar and homogenous. The International Commission of Stratigraphy and the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) set the global standards for geological timescales. We are currently living in the Holocene epoch, which is associated with human sedentism and agriculture. If all the above conditions are met, the Anthropocene could soon be defined as a new geological epoch.

Great Acceleration

Scientists are in agreement that, since the 1950s, ecosystems have been modified more rapidly and profoundly than ever before – under the combined effects of the unprecedented increase in mass consumption (in countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), dramatic population growth, economic growth and urbanization. The American chemist Will Steffen dubbed this phenomenon the “Great Acceleration”.

Great Divergence

The expression “Great Divergence”, coined by American historian Kenneth Pomeranz, designates the industrial boom that has separated Europe from China since the nineteenth century. According to Pomeranz, it was the unequal geographical distribution of coal resources and the conquest of the New World that gave the decisive impetus to the European economy.

Planet (as a unit of measurement)

The ecological footprint has a “planet equivalent”, or the number of planets it would take to support humanity’s needs at any given time. In order to determine a country’s ecological footprint, we measure the number of planets that would have been needed by the world’s population if it consumed as much as the population of that country. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), “every year, humanity consumes the equivalent of 1.7 planets to meet its needs”.

Sixth Extinction

The Great Extinction is the term given to a brief event in geological time (several million years) during which at least 75 per cent of species of plants and animals disappear from the surface of the earth and the oceans. Of the five Great Extinctions that have been recorded, the best known is the Cretaceous-Tertiary, 66 million years ago, which included the disappearance of the dinosaurs. The American biologist Paul Ehrlich has suggested that we have now entered the sixth Great Extinction (although, for the time being, its destruction in terms of number of species is considerably less than in the five others) – 40 per cent of the planet’s mammals will have seen their habitat range reduced by 80 per cent between 1900 and 2015.

Spheres

For the Russian mineralogist and geologist Vladimir Vernadsky, who devised the concept of biosphere in 1926, Planet Earth is made up of the intermeshing of five distinct spheres – the lithosphere, the rigid, rock outer layer; the biosphere, comprising all living beings; the atmosphere, the envelope of gases known as air; the technosphere resulting from human activity; and the noosphere, the part of the biosphere occupied by thinking humanity, including all thoughts and ideas. Other authors have since added to this list the notions of hydrosphere (all the water present on the planet) and cryosphere (ice).

Technodiversity

The word biodiversity refers to the diversity of ecosystems, species and genes, and the interaction between these three levels, in a given environment. By analogy, technodiversity refers to the diversity of technological objects and the materials used to make them.

Technofossils

Fossils are the mineralized remains of individuals that lived in the past. By analogy, technofossils are the remains of technological objects.

Technosphere

The technosphere refers to the physical part of the environment that is modified by human activity. It is a globally interconnected system, comprising humans, domesticated animals, farmland, machines, towns, factories, roads and networks, airports, etc.

Esmeralda Nicolicchia Remotti

To learn more:

- Crutzen P.J. (2006) The “Anthropocene”. In: Ehlers E., Krafft T. (eds) Earth System Science in the Anthropocene. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg;

- R. Harrison, C. Sterling (Ed. by) (2020), “Deterritorializing the Future Heritage in, of and after the Anthropocene”, Open Humanities Press, London;

- Head M.J. (2019), “Formal subdivision of the Quaternary System/Period: Present status and future directions”, in Quaternary International, 500, 2019, pp. 32-51;

- Lewis S.L., Maslin M.A. (2019), “Il pianeta umano. Come abbiamo creato l’Antropocene”. Einaudi 2019 Lucci A. (2018), “Thinking in the Age of Anthropocene: Cultural Heritage, Philosophical Personae, Environment”, in CPCL European Journal of creative practices in cities and landscape, 2018;

- Waters C.N., Ellis E.C., Vidas D., Steffen W. (2021), “The Anthropocene: Comparing Its Meaning in Geology (Chronostratigraphy) with Conceptual Approaches Arising in Others Disciplines”, in Earth’s Future, Feb. 2021 (con ampia bibliografia);

- Olocene, Wikipedia

- anthropocene.info