From the abjuration of Protestantism to the triumphal entry into the Eternal City: places and enterprises of a former sovereign so much loved and controversial. The woman who, in the Rome of the second half of the seventeenth century, influenced and promoted poetry, theatre, music but also science, astronomy, medicine and alchemy. As with the mythological Phoenix, from its ashes will rise the Academy of Arcadia.

Roma

The arrival of Christina of Sweden in Rome was the culmination of a long process already prepared at homeland. Christina became a sovereign, on her father’s death, in 1632.

She decided to abjure the Protestant faith in which she was raised, to embrace Catholicism, in 1652.

For this reason, the sovereign was strongly opposed in her country and finally, on 23 February 1654 she decided to abdicate and voluntarily exile herself to Rome.

As a consequence of the religious and political choices, Cristina’s journey, and the transfer to Rome, went far beyond the personal affair, fitting into the delicate balance of powers between the Catholic Church and the Protestant world.

For this, every gesture, every apparatus, every moment of the complex and articulated ceremony that accompanied the event was enriched through symbols and allegories, as usual at the time.

A first incognito entry was planned, late in the night of the 20th December, throughout the Vatican gardens ‘door called “Pertusa” , then Christina was housed in the “Torre dei Venti”, a wing of the Vatican Palaces.

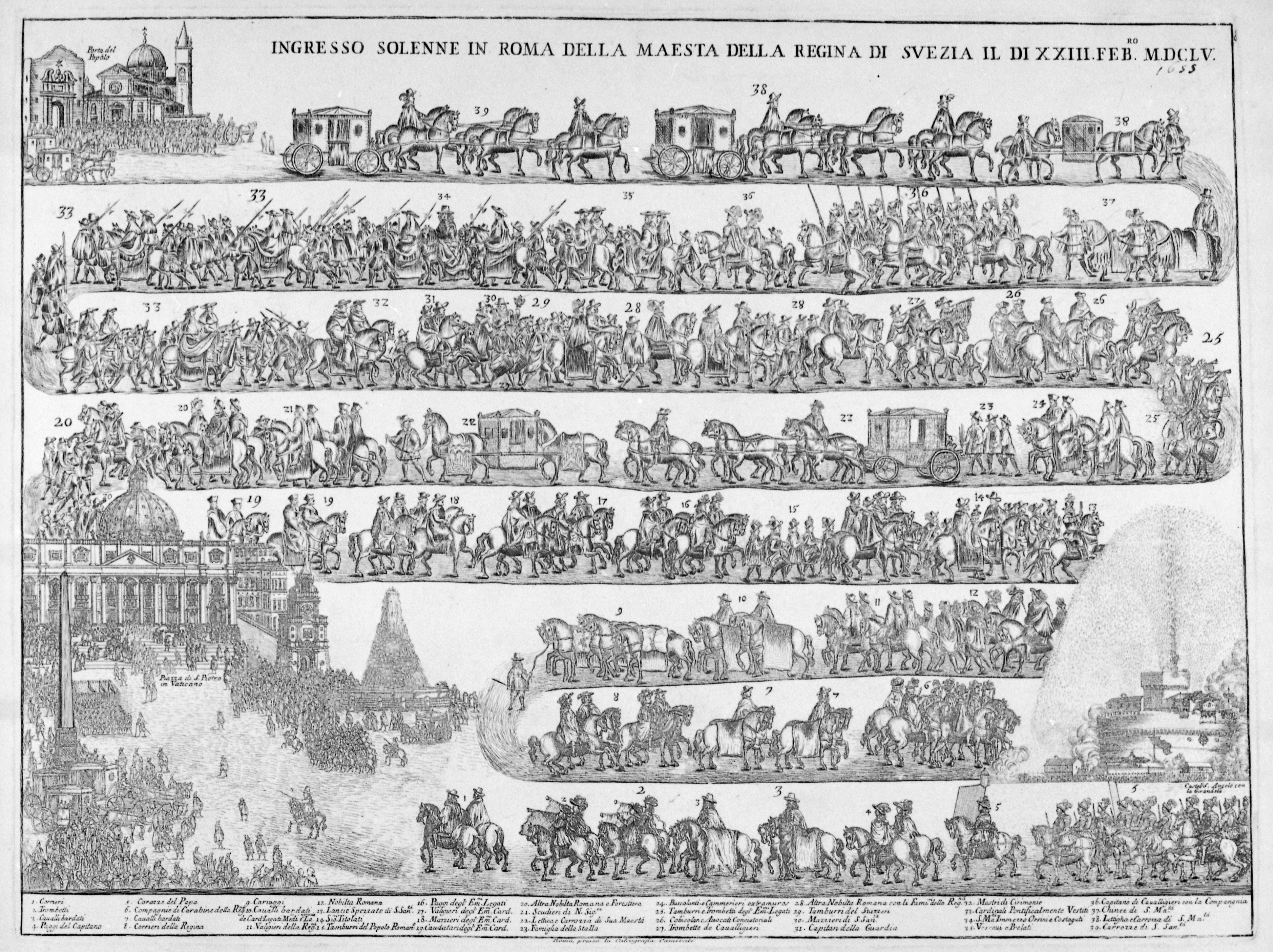

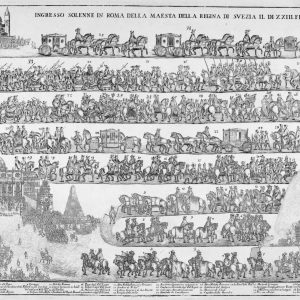

A triumphant entrance was then planned, through the “Porta del Popolo” . This involved a redevelopment of the urban spaces along which the parade would take place and the realization of those rich scenographic apparatuses and complex protocols that made so much fuss in the chronicles of the time.

On 23 December 1655, Christina made her triumphal entry into Rome through the “Porta del Popolo”, which Alessandro VII (Fabio Chigi) had Bernini restore for the occasion.

The event, as one of the most important events in the history of Rome in the seventeenth century, was immortalized with the inscription “FELICI FAUSTOQUE INGRESSUI”, placed on the top of the City Gate.

From Porta del Popolo (Porta Flaminia), the fabulous parade unfolded along “le strade del Corso, di San Marco, del Giesù, de’ Cesarini, della Valle, di Pasquino, di Parione, di Banchi, di Borgo nuovo fino a San Pietro”

(cit. da “C. Festini, I trionfi della Magnificenza Pontificia”)

The Parade

Coat of arms of Queen Christina of Sweden

Two days later, on Christmas’ day, the former sovereign was confirmed by the Pope, taking the name of Alessandra. Cristina also adopted Mary, as middle name, as requested by the pontiff, but she always signed Cristina Alessandra.

Christina’s first visits to Rome

In the days following her official entry into Rome, Christina began a long series of formal visits to the landmarks of the city:

- to the Vatican Library .

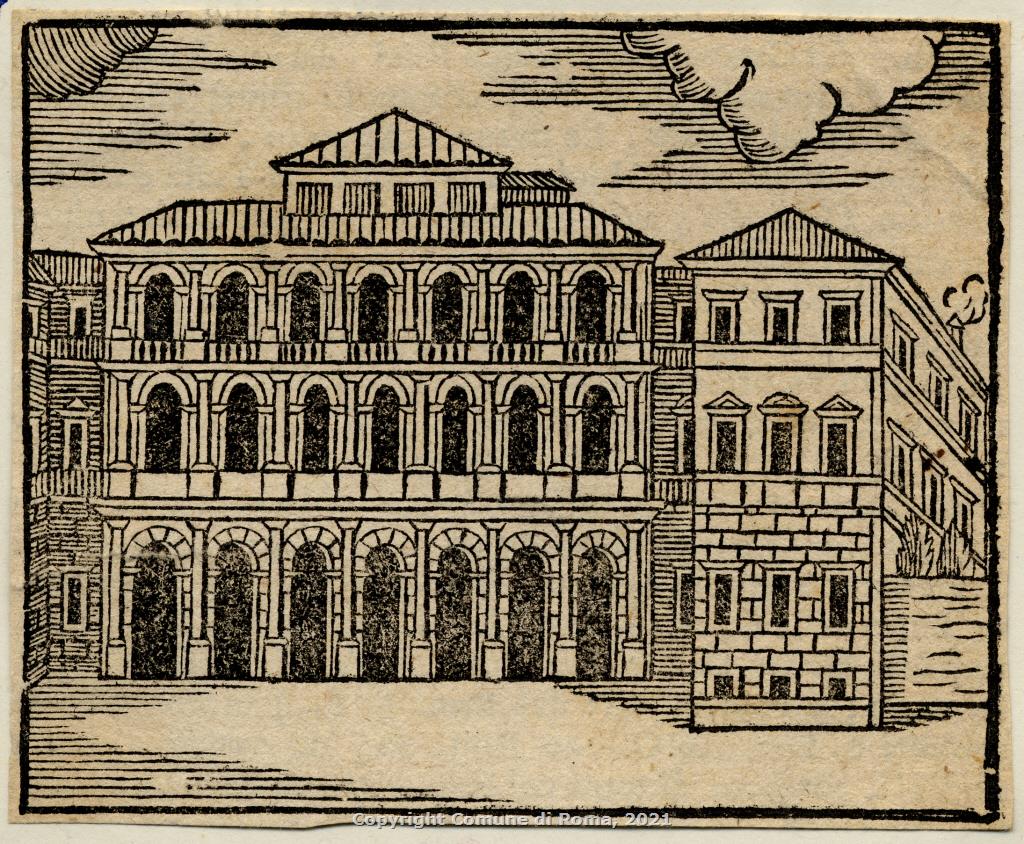

- to the “Biblioteca Alessandrina”: recently founded by Pope Alexander VII in Sant’Ivo alla Sapienzaseat of the first Roman University.

On January 14th, 1656, Christina visited La Sapienza, where she attended some lectures and received 53 books written by University’s teachers, as a gift.

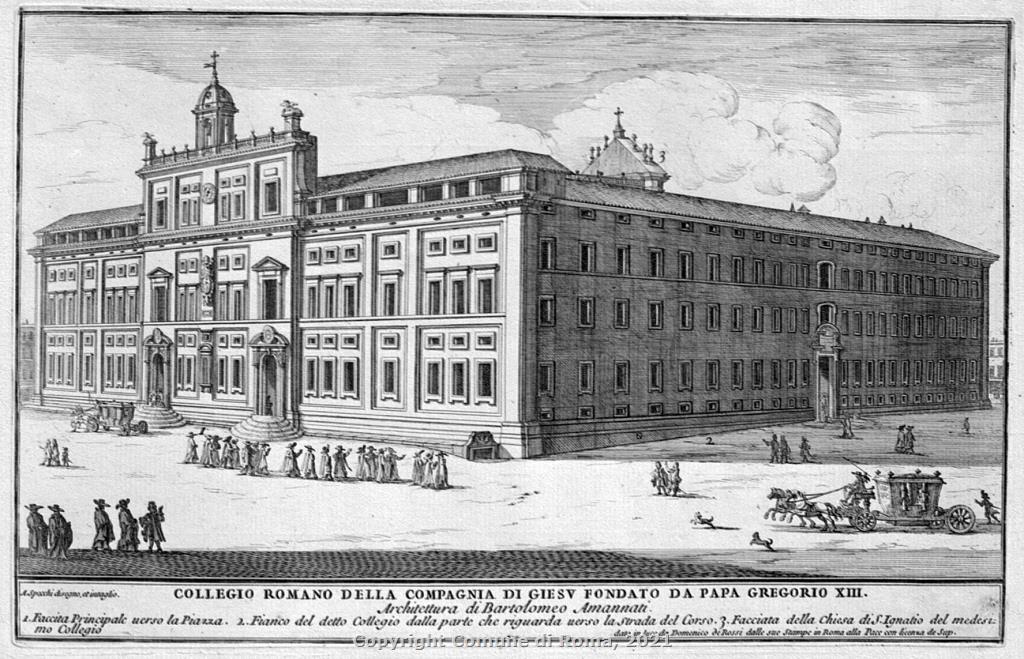

Four days later she went to the “Collegio Romano”.

“Christina left the room accompanied by the cardinal and for the same

lodge passing, stopped little space in the middle of it, near the balustrade, to see the perspective of the courtyard. She went down the same staircase on the right, passed through the right porch, stopped for a short time to take a look at the first staircase, the same as the second. Then she briefly visited the church of Sant’Ivo, stopping to observe the dome and the lantern (the upper dome) that was still under construction. She was also shown some plans and elevations of the building that had been prepared by Borromini to show them to the pope.“

Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza

- to the Collegio Romano, where she met father Athanasius Kircher, who gave her a small silver obelisk, with a commendation in thirty-three different languages. The German Jesuit, mathematician, physicist, philosopher, historian and lover of oriental languages, taught here for more than forty years and, in 1651, established a “Wunderkammer” that formed the nucleus of the Museo Kircheriano.

Athanasius Kircher Museum

browse the catalog of the Kircher Museum collection (de Sepibus 1678)

The Collegio Romano

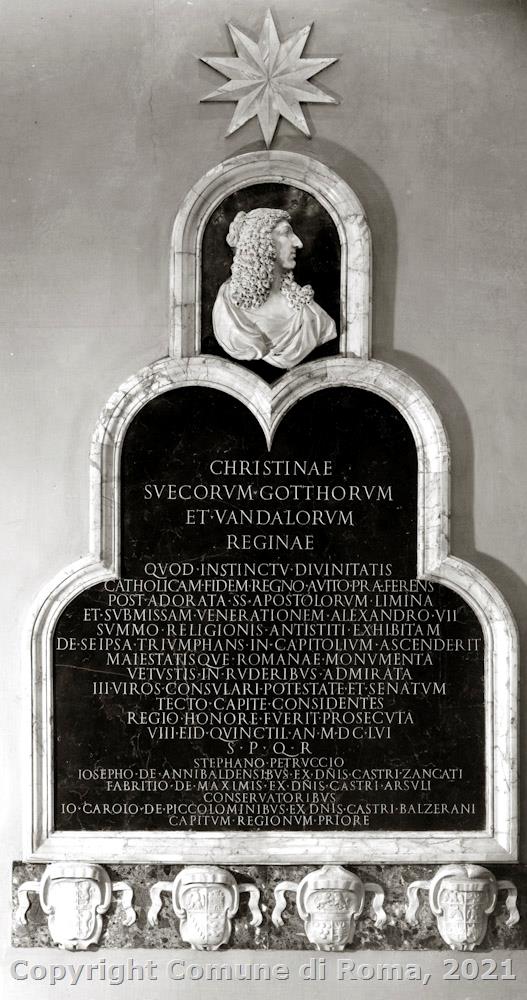

- to Campidoglio: On July 7th, 1656, Christina was received with great honors on the Capitol where, to commemorate her visit, a marble slab was placed, carved with the shape of the “mountains” of the coat of arms of Alessandro VII, with in the centre the profile of the queen crowned by the star of the Chigi.

Piazza del Campidoglio

Cola di Rienzo

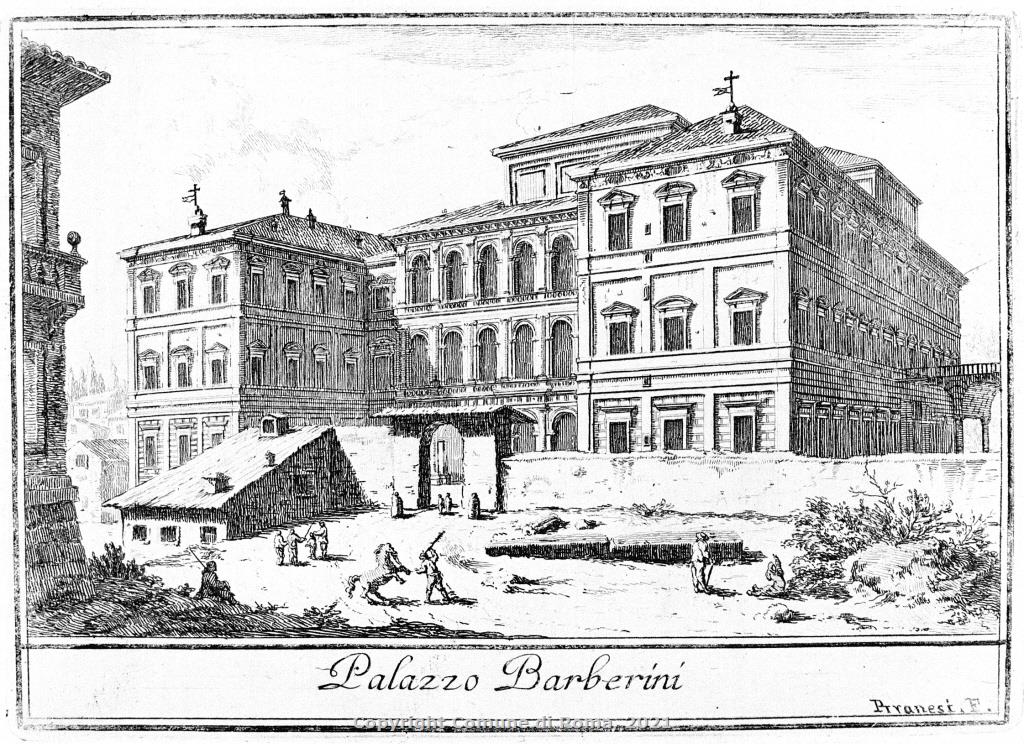

Cristina’s coming to Rome coincided with the anniversary of Alexander VII. This was the opportunity for fabulous celebrations that kept her very busy, until she officially settled in Palazzo Barberini. There she was triumphantly welcomed by a crowd of at least 6000 spectators, as well as by a long procession of camels, elephants lavishly dressed and with wooden towers placed on their backs.

Palazzo Barberini

Christina’s stay in Rome

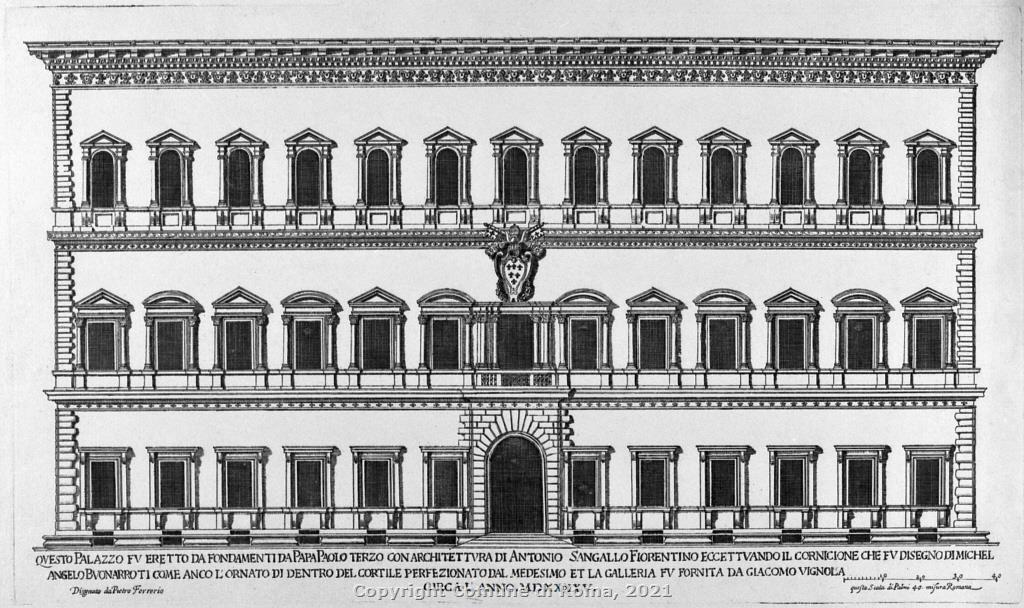

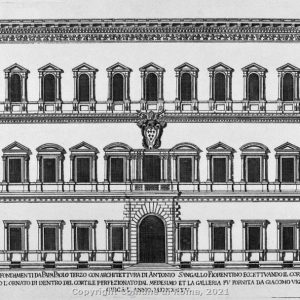

In the months to come the former sovereign stayed first at Palazzo Farnese (from December 26th, 1655), specially renovated for the occasion by the owner Duke of Parma.

Here Christina began to lead an almost irreproachable life, receiving Communion and continuing to attend churches, monasteries and monuments, but her attitude concealed in reality quite another nature. Soon she became impatient with religious practices and began to deal with art, music and entertainment, increasingly irritating Pope Alessandro VII. Cristina returned to Rome on May 15th 1658, after a series of journeys outside Italy, and resided in the beautiful , belonging to Cardinal Mazzarino. (cit. from Lovelli 2013. Ed’s tranl.)

Palazzo Farnese

During the seventeenth century, the Farnese family progressively shifted its interests in Parma; the Palace experienced a phase in which important tenants cohabited.In particular, thanks to the family’s connections to the throne of France, the residence hosted, throughout the seventeenth century, the ambassadors of Kings Luigi XIII and Luigi XIV, among these illustrious guests to remember the presence of Cardinal Alphonse-Louis de Richelieu, brother of Cardinal Armand-Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu, Prime Minister of Luigi XIII.And in this very context, on December 26th, 1655 that the transfer, in a wing of the Palazzo Farnese, of the former Queen Christina of Sweden, takes place.The eighteenth century sees a progressive dispossession of the building by the heirs of the family. In 1731, on the death of Antonio Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, Elisabetta, last heir, married to Filippo V of Spain, left the Farnese properties to her son Carlo of Borbone, first king of the Regno delle Due Sicilie, then called to become Carlo III of Spain in 1759, that began the transfer to Naples of the prestigious Farnese collection.On September 3rd,1808 Gioacchino Murat, newly elected King of Naples, received the homage of his new subjects in the Carracci Gallery.During the nineteenth century the Borbone made some changes and restorations, by the architect Antonio Cipolla, and commissioned the decoration of the rooms and dressing rooms of the piano nobile to the Grassi brothers.In 1863 Francesco II di Borbone Re delle Due Sicilie, due to the occupation of Naples by Garibaldi troops, moved into exile in Rome, in Palazzo Farnese.With the events following the capture of Rome and the Unification of Italy, the Palace became the seat of the Embassy of France, through a lease agreement with the Borbone delle Due Sicilie, followed by a purchase agreement by France.oday the French diplomatic office is still located inside the Building where, on the second floor since 1875, the Ecole Française de Rome took on institutional headquarters along with its splendid library of Archaeology and History of Art. From the twentieth century the subsequent restoration of the facade and the Palace will be taken care of by the Italian State which, exercising the right of pre-emption in 1936, took over the property, signing a lease with France for 99 years.

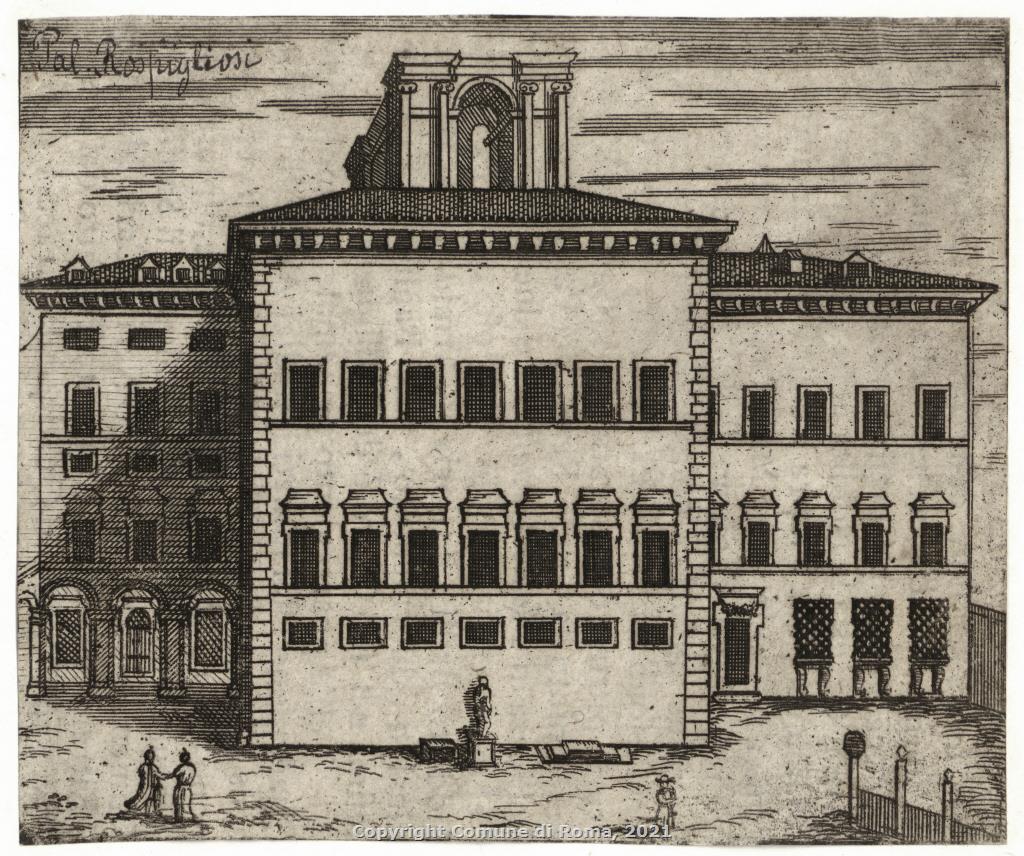

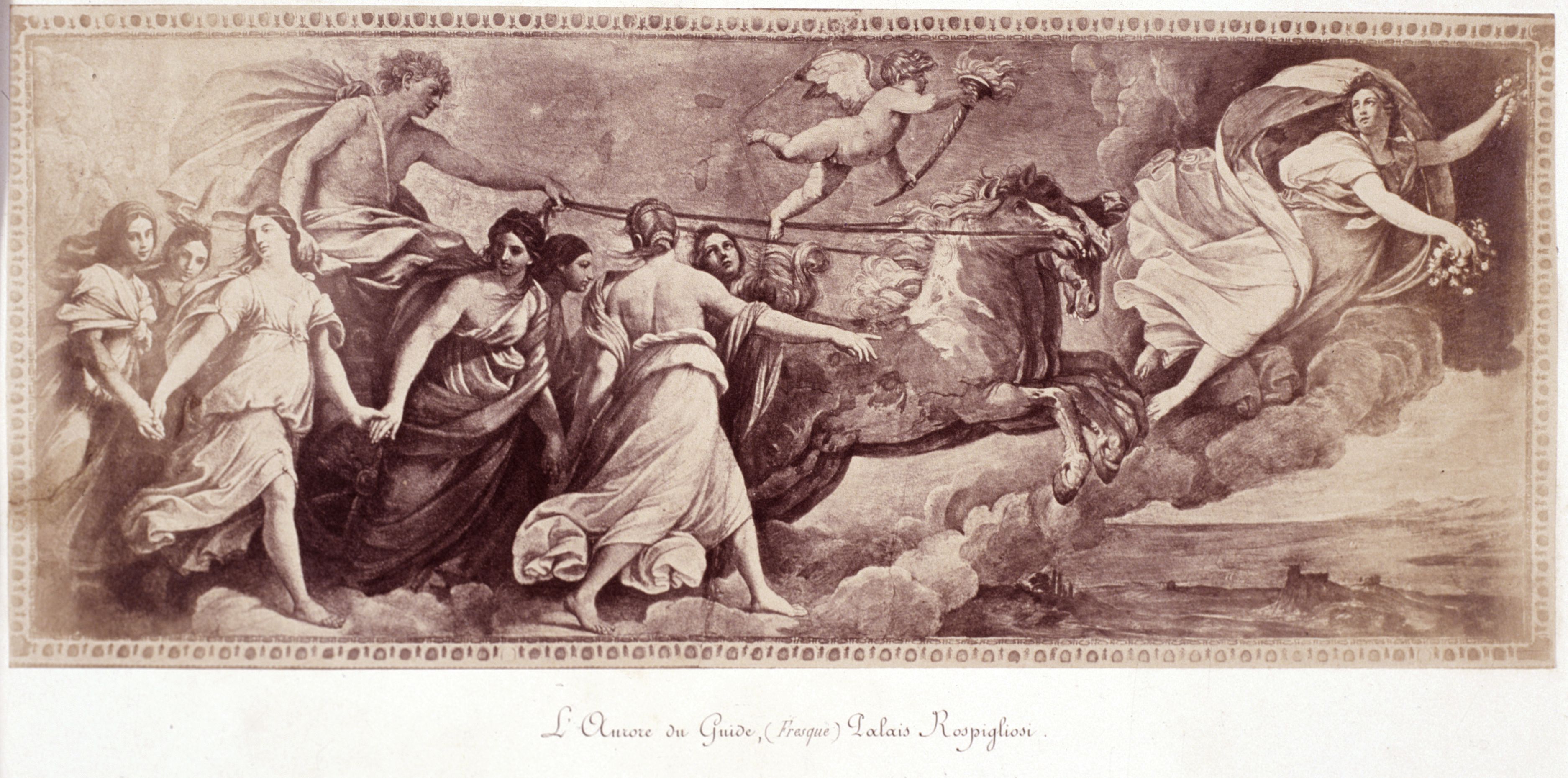

Palazzo Mazzarino – Rospigliosi

Later Christina wanted to live in the Palazzo Riario at the Lungara (now Palazzo Corsini), which she appreciated the which he appreciated the location at the foot of the Janiculum and the beautiful gardens and the location at the foot of the Gianicolo. To this aim, in March 1659, she commissioned her friend’s and collaborator, Cardinal Decio Azzolino, to arrange his installation at the Palace (Partini 2010; Lovelli 2013), of which he undertook restoration and embellishments.

Particularly dear to her was the garden, she contributed to enrich it with rare and exotic plants, forming the original nucleus of the Botanical Garden of Rome, where you can still admire some plane trees dating back to the time of the sovereign.

During the restorstions, first years were spent by Christina in a secondary house, now no longer existing: a rural casino near the Palace, where she moved till the completion of the works in 1663.

Having become his definitive residence, Christina placed her small and varied court in the palace that soon became the seat of intrigue, diplomatic travels, parties and gallant adventures, but also of important intellectual relations: in 1674 the Royal Academy was founded, to which was added an Academy of Physics, Natural History and Mathematics.

Love and interest for the arts and for sciences and the innate patronage of this cultured and intelligent woman, were the foundations from which the Academy of Arcadia was born, immediately after her death and in her memory.

Palazzo Riario at the Lungara

The patronage of the former sovereign – Theatre, music and Baroque parties

From the very beginning of her stay in Rome, Christina distinguished herself by her perfect patronage, surrounded by musicians, artists and writers including Alessandro Scarlatti, Arcangelo Corelli, Bernardo Pasquini ed i poeti Alessandro Guidi e Vincenzo Filicaia.

In 1670, with the help of Conte Giacomo d’Alibert, she founded the Tor di Nona Theater .

The Tor di Nona Theatre

The Carousel Parade at Palazzo Barberini – February 29th, 1656

The presence of Christina offered the opportunity for the preparation of sumptuous feasts, an occasion immediately took by the most powerful families who contended for the primacy of power of which Rome was undisputed representative.

So the Barberini, recently back from France, on the occasion of the Carnival of 1656 organized an event destined to remain famous in the local chronicles, and not only.

“The Carnival Carousel is held ideologically and allegorically, in a decidedly different way from the Saracen Carousel of ’34. First of all, the chosen place: no longer a famous town square but the courtyard of the family Palace (Palazzo Barberini alle Quattro Fontane n.d.r.).

A tighter and more collected space, in its theatrical values, that proposed in terms of nostalgia the refined option of princely courts of the sixteenth and of the early seventeenth century, for more exclusive outdoor shows and courtiers. There the courtyard-square value was a decisive model for the development of the theater room itself, with the upper gallery or windows overlooking the courtyard to suggest a vertical use.

The Cortile della Cavallerizza, on which the monumental entrance to the Palazzo was on the side of the City, closed by a long wall and which was accessed through the majestic portal of Pietro da Cortona overlooking the former Piazza Grimana, now Barberini, presented himself as a real princely court. In this sense the “Teatro della Comparsa” will be set up, demolishing for the occasion also some houses.”

(cit. from Chiappara 2014, Ed’s transl.)

For the occasion Giovan Francesco Grimaldi was in charge of the project of the theatre, the costumes, the harness of the horses and the machines.

An essay on the spectacular nature of the planned program can easily be imagined from the description of the events that left to us Conte Galeazzo Gualdo Priorato in his “Historia” upon Queen Christina of Sweden:

“On February the 28th evening’s, the Carousel Joust began with the entry into the courtyard of the two teams of riders who were to face each other, with their respective wagons. They are the Romans, dressed in silver and blue, followed by the chariot of Roma-Amore pulled by the Grazie, and the Amazzoni, in red and gold dresses, followed by the chariot of Indignazione pulled by the Furie… After a music Dialogue, began the carousels of knights with rich costumes and very high hairstyles with coloured plumes. Highlight of the show is the entrance of the Hercules’ chariot, a horrifying Dragon shaped machine. This, with Hercules on his back, dressed with the skin of the lion Nimeo, accompanied by maidens who distributed golden apples of the Esperidi, vomited burning flames. Finally, the Sun Chariot triumphantly entered, represented as a shining divinity with the four seasons and the twenty-four hours at its feet”.

(cit. da Chiappara 2014, Ed’s transl.)

Evidence of the great “media” echo of the event can be found in the large painting of Filippo Gagliardi and Filippo Lauri, now in the Museum of Rome.

In February 1689, Christina became seriously ill; the certainty of a near end prompted her to write a letter to ask the pope forgiveness for all the troubles she had caused. Her strong nature kept her alive until April when, due to a bad relapse, she died at six in the morning of the 19th. In her will she named Cardinal Azzolino sole heir. It wasn’t even two months that he followed her too, leaving the inheritance to his nephew Pompeo Azzolino.

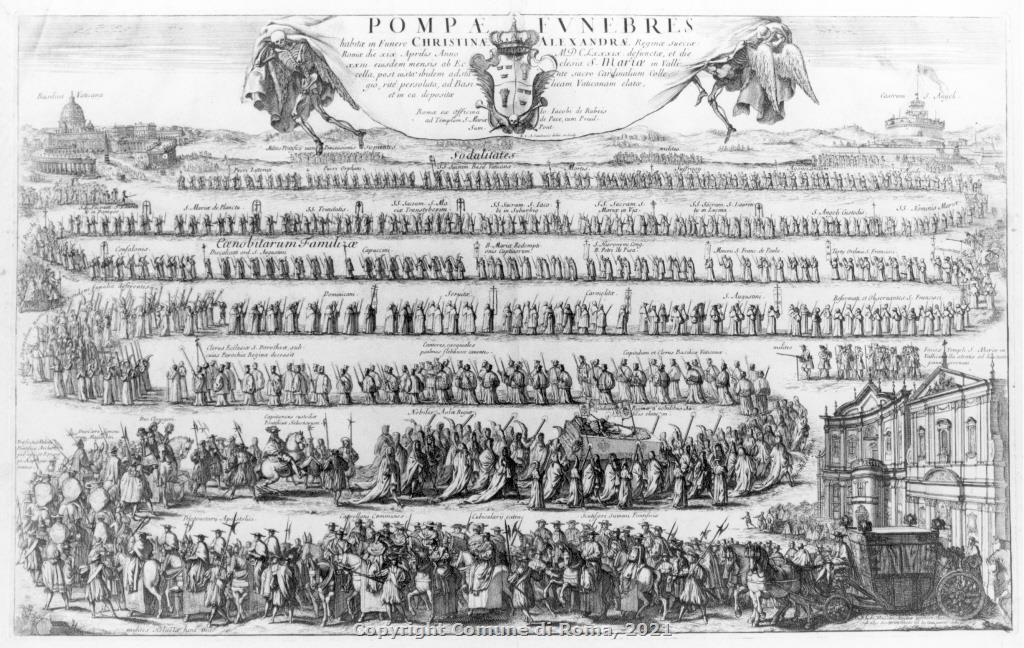

Cristina had appointed the Pope as her will executor. He set up a four-day funeral vigil at Palazzo Riario and ordered a solemn funeral to be celebrated in the Church of Santa Maria in Vallicella . Christina was placed on a sumptuous canopy, in the centre of the nave illuminated by three hundred torches, with the royal crown on her head, for the last farewell. Then, she was buried, always by Pope’s claim, inside the Vatican Grottoes , below Saint Peter’s Basilica 13. , next to the remains of Matilda of Canossa (1046-1115) (Lovelli 2010).

n 1696, in honour of the late sovereign, Pope Clemente XI had a monument built by the architect Carlo Fontana, to commemorate her wonderful conversion and as a sign of gratitude of the city of Rome. It was finished in 1702 and placed inside the Vatican Basilica.

Esmeralda Nicolicchia Remotti

Bibliografia

- Carlo Festini, Trionfi della Magnificenza Pontifica celebrati per lo passaggio nelle Città e luoghi dello Stato Ecclesiastico e in Roma per lo ricevimento della Maestà della Regina di Svetia, Roma,

- Stamperia della Rev. Camera Apostolica, 1656.

- Giorgio de Sepibus, Romani collegii Societatis Jesu musaeum celeberrimum, Romae, ex Officina janssonio-waesbergiana, 1678, antiporta.

- Galeazzo Gualdo Priorato, Historia della Sacra Maestà di Cristina Alessandra di Svezia, Roma, 1656

- Carboni L, “Documenti di e su Cristina di Svezia nell’archivio segreto vaticano”, in Platania G. (a cura di), Roma e Cristina di Svezia. Una irrequieta sovrana. Sette Città, 2016, Un. Tuscia, Viterbo, pp. 209 – 248

- Chiappara I., “La Giostra del Saracino del 1634 e la Giostra dei Caroselli del 1654. Il mecenatismo dei Barberini e Marco Marazzoli”. Soria 2014.

- De Caprio F., “L’entrata in incognito di Cristina di Svezia in vaticano: cerimoniali e simboli”, in Settentrione n.s., Rivista di Studi Italo-finlandesi, n.30, anno 2018, pp. 187 – 211

- De Caprio F., “Il primo soggiorno romano di Cristina di Svezia attraverso il Diario di Carlo Cartari”, in Lanzetta L. (a cura di), La storia o/e le storie nel Diario di Carlo Cartari avvocato concistoriale romano. Istituto Nazionale di Studi Romani, LuoghInteriori, Città di Castello, 2019

- Di Palma W., “Cristina di Svezia: Scienza ed alchimia nella Roma barocca”, in Atti del Ciclo di Conferenze (Roma, Sala Borromini, 17 – 19 aprile 1989) sulla cultura scientifica alla corte romana di Cristina di Svezia, nuova biblioteca dedalo 99: serie nuovi saggi. Bari, Dedalo, 1990, pp. 18, ss.

- Lovelli G., “Cristina di Svezia: una regina anticonformista”, in Viaggio e soggiorno romano di una regina: Cristina di Svezia, n. 005, Società e chiesa del 1600. 13 Ottobre 2013. .

- Partini A. M., “Cristina di Svezia e il suo Cenacolo Alchemico”. Roma, Ed. Mediterranee, 2010

- Platania G. (a cura di), Roma e Cristina di Svezia. Una irrequieta sovrana. Sette Città, 2016, Un. Tuscia, Viterbo

- Guzzi P., “Il teatro a Roma. Tre millenni di spettacolo”. Roma, Rendina Editori, 1998. voce Teatro Tordinona, da Wikipedia.